An analysis of more than 17 million people in England — the largest study of its kind, according to its authors — has pinpointed a bevy of factors that can raise a person’s chances of dying from COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus.

The paper, published Wednesday in Nature, echoes reports from other countries that identify older people, men, racial and ethnic minorities, and those with underlying health conditions among the more vulnerable populations.

“This highlights a lot of what we already know about COVID-19,” said Uchechi Mitchell, a public health expert at the University of Illinois at Chicago who was not involved in the study. “But a lot of science is about repetition. The size of the study alone is a strength, and there is a need to continue documenting disparities.”

The researchers mined a trove of de-identified data that included health records from about 40% of England’s population, collected by the United Kingdom’s National Health Service. Of 17,278,392 adults tracked over three months, 10,926 reportedly died of COVID-19 or COVID-19-related complications.

“A lot of previous work has focused on patients that present at hospital,” said Dr. Ben Goldacre of the University of Oxford, one of the authors on the study. “That’s useful and important, but we wanted to get a clear sense of the risks as an everyday person. Our starting pool is literally everybody.”

Goldacre’s team found that patients older than 80 were at least 20 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than those in their 50s and hundreds of times more likely to die than those below the age of 40. The scale of this relationship was “jaw-dropping,” Goldacre said.

Additionally, men stricken with the virus had a higher likelihood of dying than women of the same age. Medical conditions such as obesity, diabetes, severe asthma and compromised immunity were also linked to poor outcomes, in keeping with guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States. And the researchers noted that a person’s chances of dying also tended to track with socioeconomic factors like poverty.

The data roughly mirror what has been observed around the world and are not necessarily surprising, said Avonne Connor, an epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins University who was not involved in the study. But seeing these patterns emerge in a staggeringly large data set “is astounding” and “adds another layer to depicting who is at risk” during this pandemic, Connor said.

Particularly compelling were the study’s findings on race and ethnicity, said Sharrelle Barber, an epidemiologist at Drexel University who was not involved in the study. Roughly 11% of the patients tracked by the analysis identified as nonwhite. The researchers found that these individuals — particularly Black and South Asian people — were at higher risk of dying from COVID-19 than white patients.

That trend persisted even after Goldacre and his colleagues made statistical adjustments to account for factors like age, sex and medical conditions, suggesting that other factors are playing a major role.

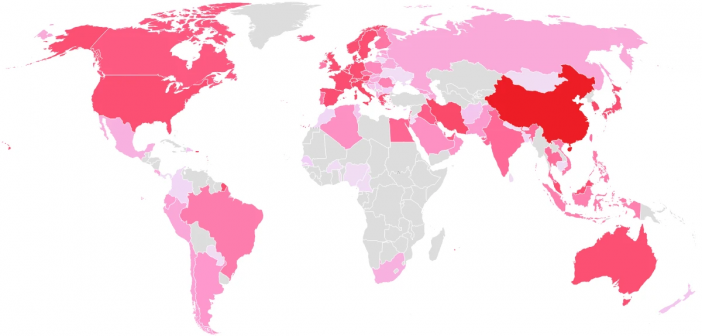

An increasing number of reports have pointed to the pervasive social and structural inequities that are disproportionately burdening racial and ethnic minority groups around the world with the coronavirus’s worst effects.

Some experts pointed out flaws in the researchers’ methodology that made it difficult to quantify the exact risks faced by members of the vulnerable groups identified in the study. For instance, certain medical conditions that can exacerbate COVID-19, like chronic heart disease, are more prevalent among Black people than white people.

The researchers removed such variables to focus solely on the effects of race and ethnicity. But because Black individuals are also more likely to experience stress and be denied access to medical care in many parts of the world, the disparity in rates of heart disease may itself be influenced by racism, said Usama Bilal, an epidemiologist at Drexel University who was not involved in the new analysis. Ignoring the contribution of heart disease, then, could end up inadvertently discounting part of the relationship between race and ethnicity and COVID-19-related deaths.

The study was also not set up to conclusively show cause-and-effect relationships between risk factors and COVID-19 deaths.

Regardless of the methodological drawbacks of this study, experts agree that “the causes of disparities, whether in COVID-19 or other aspects of health, are intricately linked to structural racism,” Mitchell said.

In the United States, Latino and African American residents are three times as likely to become infected by the coronavirus as white residents, and nearly twice as likely to die.

Many of these individuals work as front-line employees or are tasked with essential in-person jobs that prevent them from sheltering in place at home. Some live in multigenerational households that can compromise effective physical distancing. Others must cope with language barriers and implicit bias when they seek medical care.

Any study publishing data on an ongoing and fast-shifting pandemic will inevitably be imperfect, said Julia Raifman, an epidemiologist at Boston University who was not involved in the study.

But the new paper helps address “a real paucity of data on race,” Raifman added. “These disparities are not just happening in the United States.”

With regard to the racial inequities in this pandemic, Barber said, “I think what we’re seeing is real, and it’s not a surprise. We can learn from this study and improve on it. It gives us clues into what might be happening.” ♦